The market gets what it wants

One thing the central bank cannot do: Refuse market sentiment.

Novelties in central banking since 2007/08 have seen much discussion. But the introduction of somewhat overlooked permanent central bank liquidity swap lines can shed a light onto future monetary policy, such as a standing repo facility.

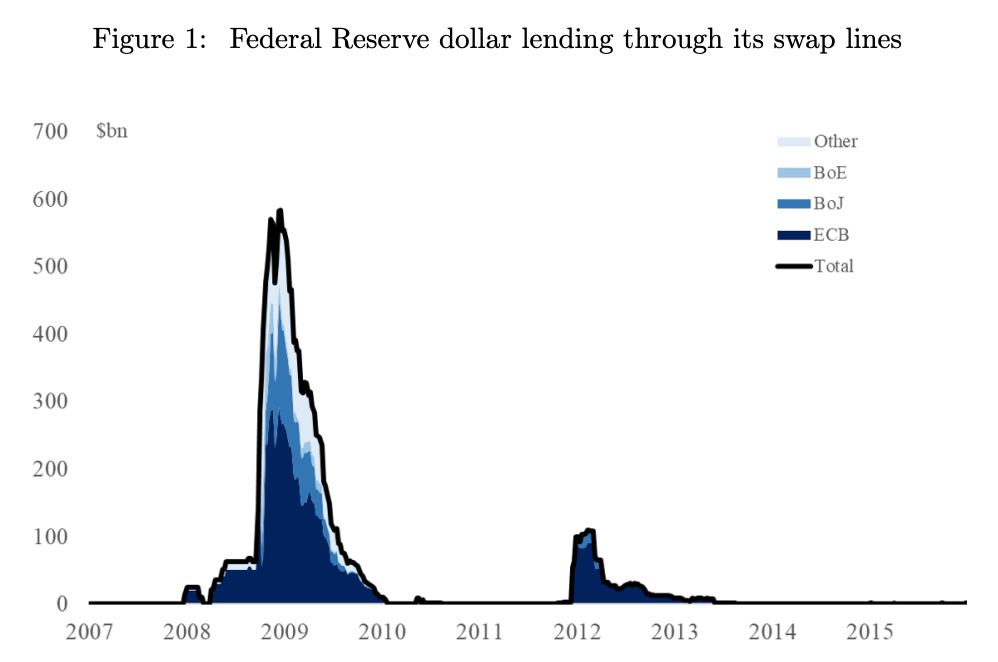

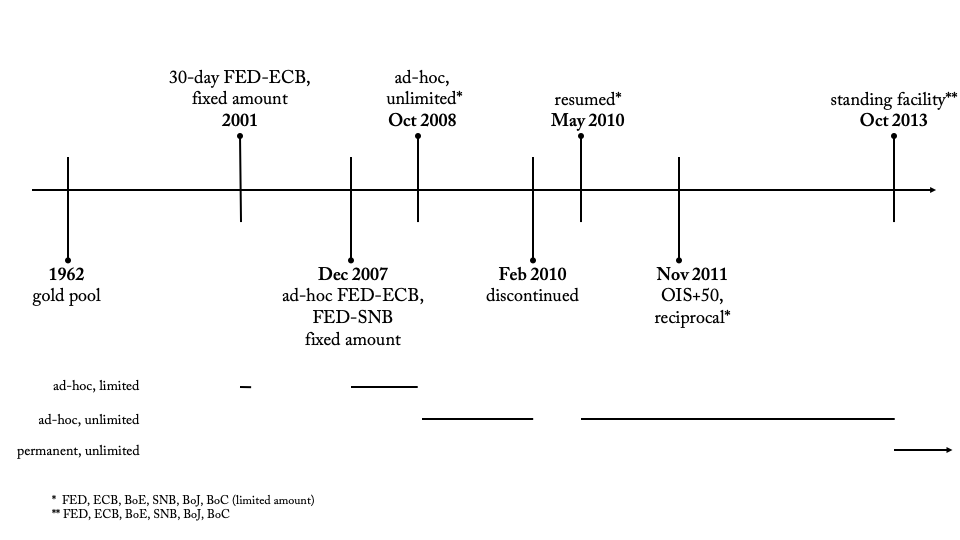

The lines were first introduced in December 2007, when the Fed and the ECB and the Fed and the SNB swapped currencies so that the off-shore central banks could provide their banks with greenbacks. The Fed extended this facility in the turmoil of 2008 but most importantly the feature became a permanent backstop to Eurodollar markets in October 2013.

The swap lines that the Fed set up with the Bank of England, European Central Bank, Swiss National Bank, Bank of Japan and Bank of Canada (together the C6) now are unlimited, permanent and reciprocal. Furthermore, all participating central banks share the same agreements amongst each other. European and Japanese banks are using the dollar allotments at their respective central banks on a weekly basis, albeit at small amounts. And the BoE in March of 2019 drew on this agreement when it activated its line with the ECB.

Image from Bahaj, Reis (2019)

Ad-hoc international lending of last resort was already common before financial journalist and monetary theorist, Walter Bagehot, urged central banks to provide liquidity during a squeeze. Take, for instance, the case of winter 1857 when the Austrian National Bank sent a train carriage full of silver to the free city of Hamburg. The Hansestadt had been running very low on silver reserves. A liquidity crisis there saw merchants unwilling to clear their shipments. Anecdotal reference holds, that as the train arrived and took a turn through the city, trust was re-established and money changed hands again.

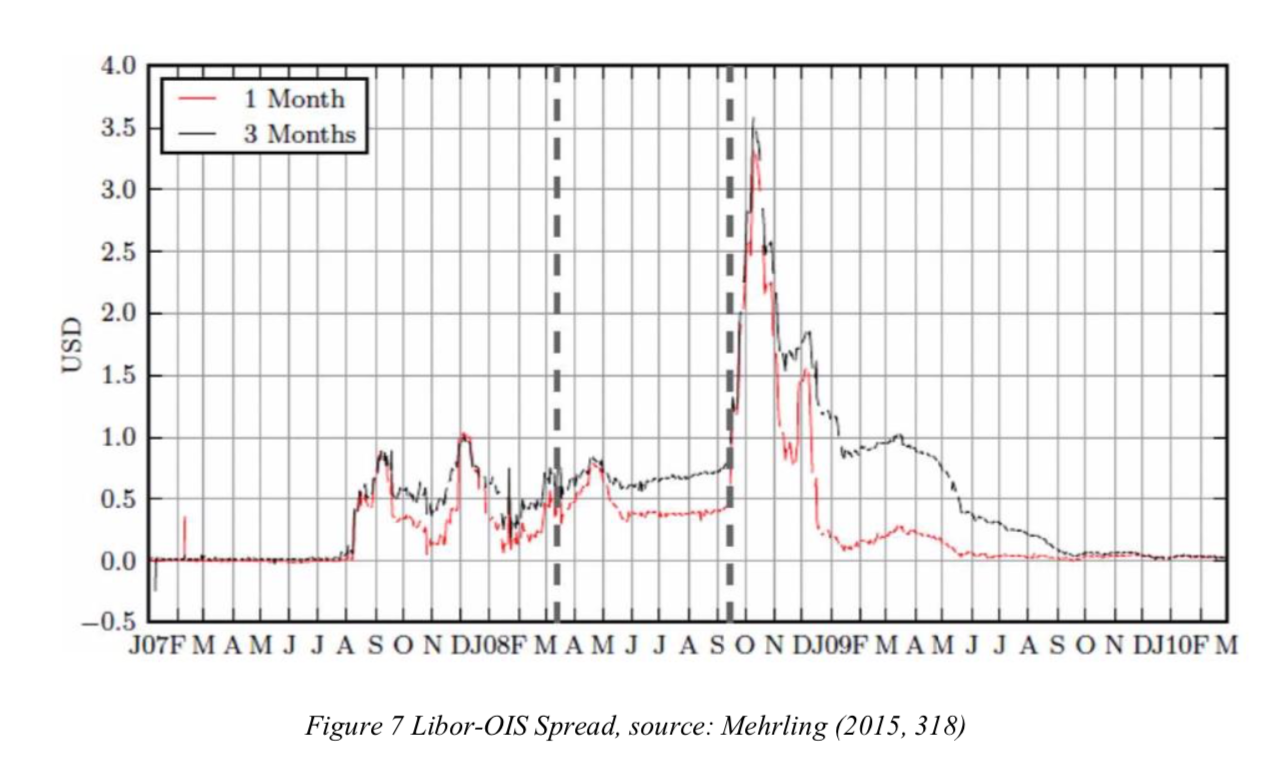

The example with missing silver in Hamburg but excess silver in Vienna exemplifies what happened in the 2007/08 Eurodollar squeeze. European banks that had funded their dollar portfolios short-term saw a hike in funding costs after French bank BNP Paribas closed access to three of its hedge funds. These increased costs meant a liquidity crisis for European banks, as they were able to access Euros, but not dollars, from the ECB.

Swap lines between central banks fixed this issue from December 2007 onwards. That the network of swap lines between six central banks became permanent in 2013 fixed the missing backstop to Eurodollar markets and put a cap on funding costs.

Three lessons for broader monetary policy can be learned by studying the process that led to the 2013 decision.

First, who is part of the major-currency backstop-club is a question of geopolitics. Most studies on swap lines by political economists find that alignment with US interests of capital account openness or exposure of US financial institutions were key determinants on whether Emerging Market central banks received a Fed swap line during the crisis. The C6 club, however, was less formed by economic determinants or foreign policy preferences. As a former Fed official tasked with setting up the swap line network again during the wake of the Eurocrisis in 2011 told me, the Bank of Canada for one was simply included because they had been part of the club before. No further questions asked. The previous institutional setting was simply sticky, a facet of the international financial architecture which the Amsterdam political economist Marieke de Goede calls „frozen power structures“.

Third, the facility became permanent, once the market simply expected it to be there. Initially, swap-lines were introduced to reduce stress in the market and create certainty about funding. Reassuring markets also featured as the main concern when Fed staff moved a decision on prolonging temporary swap-lines to an earlier meeting. They were concerned that “as the deadline grew closer, the markets would start to worry about whether the swap-line was going to be there or not,“ as one of the designers of the tool, Nathan Sheets, argued in 2010. Swap lines were extended again and again because “allowing the swap-lines to expire would seem to create unnecessary risks,“ as Brian Sack, then manager of the New York Open Market Account, put it. In October 2013 the same argument was used to justify the permanent introduction of the feature. Staff to the FOMC contended that standing lines would “reduce uncertainty among market participants as to whether and when these arrangements would be renewed and would limit the risk that decisions regarding the renewal of these arrangements would be misinterpreted.”

These three lessons shed light on the debated standing repo facility. Former NY Fed chairman Bill Dudley now calls for such a tool that updates the lender of last resort facility to current market environments. Just as liquidity swap lines cap deviations from covered interest parity, a permanent Fed repo would cap repo rates. And just like swap lines solve dislocations in Eurodollar funding, the Fed repo counters pass-through issues with domestic reserves.

If decision-making follows the in the same vein as it did with the swap lines, the standing repo facility will be there soon, just as analysts at Deutsche Bank and Citi have already argued last year. The Fed has intervened again and again and tasked the trading desk at the NY Fed to do so „until instructed otherwise“. The market will soon simply expect it to be there. It will then be more costly for the Fed to dismantle the facility than to perpetuate it. And just like with swap lines, Fed officials will warm to the understanding presented by Dudley: The Fed earns on Treasury holdings more than it pays on reserves issued to banks. And lastly, a standing repo facility will perpetuate power structures within International Finance. Choosing the five partners for the C6 swap lines followed a momentum of old Basel Club friends. The backstop to the repo market will strengthen the position of US primary dealers vis-à-vis money market participants elsewhere.