Geoeconomics on TikTok season 1

I think it is power that excites people about economics.

For this series, a team at DW put together visual first, 3 minute TikTok videos; stories of “geoeconomcis”.

The term is a catchphrase. I think of it as a refocussing on what Susan Strange did. The journalist brought a practicioner’s perspective to studying International Political Economy. My guiding principle for telling these stories was: Something in the economy happens here, it affects politics in this other place. Or vice versa.

The initial season ran for five episodes.

Why the US is loosing to China at sea

This series wouldn’t have been possible without an amazing team of creative people, designers, editors, authors, planners.

Mentally, my first episode is our “shipbuilding”-piece. It’s a story about a stark realisation within the White House since at least Biden, that the United States is loosing to China at sea. Chinese shipyards are continuously pumping out larger shares of the global market for boats – container ships, the like.

To counter, U.S. administrations have taken steps in the past to finance further capacities and had at some point threatened to put levys on docking Chinese ships. As of right now, this threat is off the table as far as I can tell – as part of the China-US trade war truce of October 2025.

@dwnews What if the key to US military dominance is workers, not weapons? The US wants to build enough ships to rival China, but does it have the manpower to do so? We dive deep on why the two countries want to dominate shipbuilding. #dominomics #MAXAR #CSIS #MaritimePower #USChinaTensions #shipping #trump #trade ♬ original sound - DW News

Why the EU’s energy dependence on the US is quirky

We fell in love with sounds for this series and realized how much atmo work creates a whole multimedial space to explore a story.

The “LNG”-episode added props to the storytelling. Shoutout to Anna and Jorana for »Regie« and everything else. This story starts in Zeebrugge, on Belgium’s coast. Structures in the sea there form a vital entrance point into Europe’s gas market.

Since shunning Russia’s energy, European Union countries increasingly bought LNG from the United States. A dependence, that is more fragile than Europe’s dependence on Russia.

@dwnews The EU is open to buying more US LNG to placate Donald Trump and dodge exorbitant tariffs. The bloc has become far more reliant on US LNG in recent years, having massively cut its reliance on Russian gas following the invasion of Ukraine. Is the EU merely trading one gas dependency for another? #dwnews #dominomics #unitedstates #russia #lng ♬ original sound - DW News

How Europe became dependent on China for rare earths

This story starts at a rare earths trader in Berlin. Very exciting for me, because I hadn’t seen rare earths before but written about them a couple of times.

We wanted to have “on-the-ground” elements for this series because we believe, reporters should see things with their own eyes. How do you make Terbiumoxide palpable? It looks kind of like cocoa powder.

Special treat that the TV-version of the piece, shoutout to my colleague Katharina, was featured in German broadcaster ZDF’s late night show “Heute Show” in October 2025 [Section from 11:54.

Special treat that the TV-version of the piece, shoutout to my colleague Katharina, was featured in German broadcaster ZDF’s late night show “Heute Show” in October 2025 [Section from 11:54.

The TikTok piece traces the supply chain for some rare earths: From the trader’s place in Berlin to the mountains of Myanmar.

@dwnews China controls the world's rare earth minerals – and it’s now flexing its muscles. It's restricted exports to the US, the EU, and even India, hurting their auto industries among other things. How did China build this dominance and what does it mean for the rest of the world? A German warehouse may hold the answer. #dominomics #RareEarths #China #EU, #US, #criticalminerals #geopolitics ♬ original sound - DW News

The boxes making US trade uneasy

The problem in a series on geoeconomics is: How can audiences connect to the thing we talk about. For this one, my colleague Kristie chose cardboard boxes.

As an early warning indicator, her piece in September forshadowed a structural recession in the United States. At time of writing this in November 2025, we’re looking spot on.

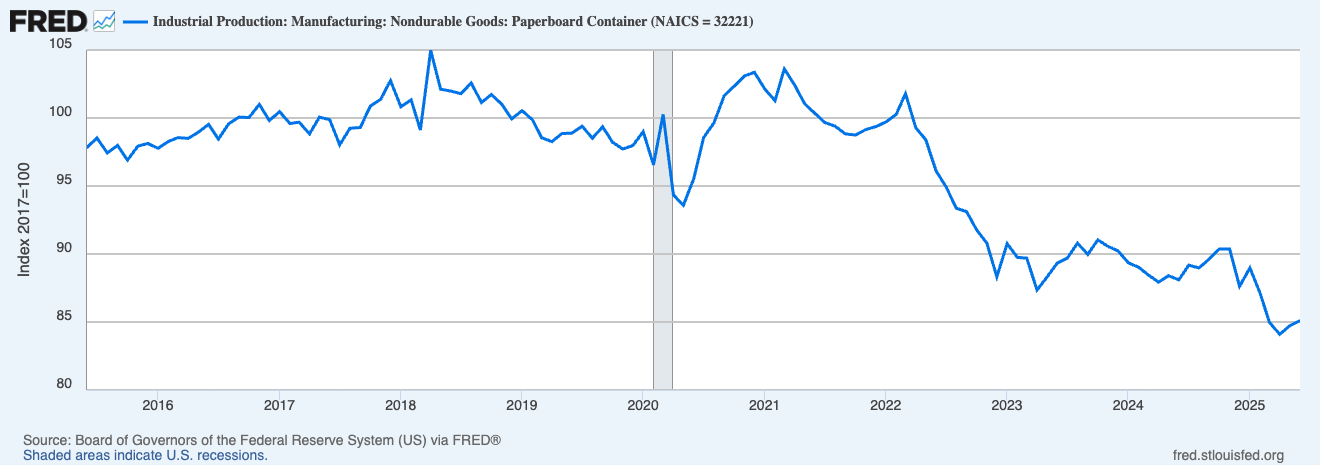

One thing I love about this series is to play with data. Kristie and Jorana in this piece wonderfully show how data on cardboard box production develops over time by flying through the timeline. It’s the chart below.

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

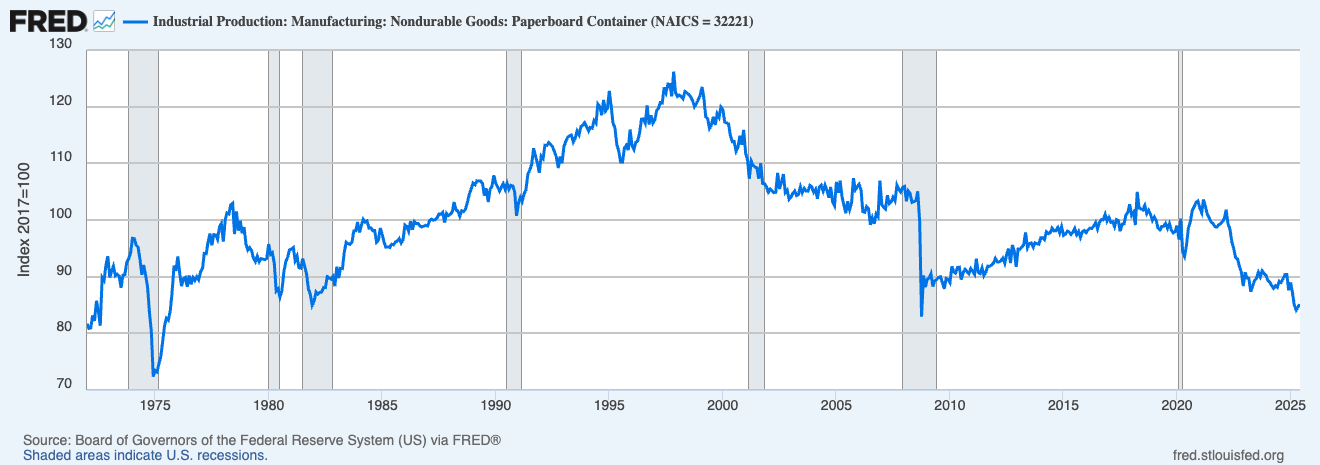

This time travel idea gave me an idea. I thought, what happens if we go back in time? The blow chart shows the same indicator but how it developed since 1972.

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

I want to now know: What did this day in November 1997 look like, when cardboard box production soared highest to 126.1693.

Here’s from the St. Louis Fed blog on the downward trend:

“Sustainability requirements, lightweighting technology, and consumer preferences have yielded significant changes in the industry, including a shift from virgin to recycled capacity. Many companies also factor-in packaging size to try to minimize impact on landfills, shipping, and warehouse inventory. Despite its recyclability and decomposition properties, cardboard takes up more space than, say, a plastic bag or other flexible packaging that incorporates both foil and plastic.

Also consider inventory positions and the economy in general: Back in 2020-21, there were shortages of virtually everything. Manufacturing played catch-up, eventually exceeding demand. Customers overbought based on inflated demand signals, resulting in full warehouses and stores in an economy with consumers purchasing less due to inflationary pressure. This may partly explain the large dip in 2022. Put simply, if fewer products are being produced, purchased, and shipped, then less cardboard is needed and thus produced.”

There’s something else, I’d like to throw into the ring for the structural reversal of paperbox production: I’d argue our lives in general have become more digital. Since the nineties, early 2000s we buy digital things. In the beginning it was ringphones for you cell. Now its apps and yoga classes.

@dwnews Uncertainty is rippling through the US economy as Trump’s tariff war leaves manufacturers guessing and consumers hesitating. Even the cardboard boxes that move goods around the country are flashing warning signs. #dwbusiness ♬ Originalton - DW News

The German company at a forkroad for Chinese chipmaking

Like no other company, Zeiss sits at the core of making the most advanced microchips in the world. Together with Dutch company ASLM, they make the crucial tools to create thin silicon wavers that later allow to calculate data.

The piece seemed to have hit a nerve and highlights one of the amazing strengths of DW: It wasn’t just 1.2 Million English users who saw the video on TikTok. In collaboration with our Spanish desk, the video drew crowds on their platforms and subsequently in a whole range of DW’s 32 languages.

I think Siemens due to their nuclear tech and Airbus are close contenders to be covered next.

@dwnews Germany's Zeiss SMT plays a key role in producing the most advanced chips on the market. Their optics are essential parts of the chip-making machines produced by the Dutch company ASML. These machines are the most advanced machines in the world, and the US does not want to see them in Chinese hands. However, it's unclear if the US's pressure on Europe to restrict sales of these machines to China will hold the country back in the long run. Due to export restrictions, the most advanced chip-making tech, so-called extreme ultraviolet (EUV) and the even newer high NA-EUV lithography machines are out of reach for the country. But reports suggest that Chinese companies are testing domestic alternatives that could help them catch up to the technology currently dominated by Zeiss and ASML. #dominomics #dwbusiness #ChipWar #semiconductor #USChina ♬ original sound - DW News